Hello, I am Dr. David Jamison

I am an Activist and Public Educator

View My Latest Article

The Tampa Tribune

December 2, 1921

You think the past has no connection to the present?

The above articles are referring to a scandalous murder trial that happened here in Jacksonville, Florida, over a hundred years ago. Perhaps there is no more blatant a case of the loss of generational wealth than the case of the Lang family.

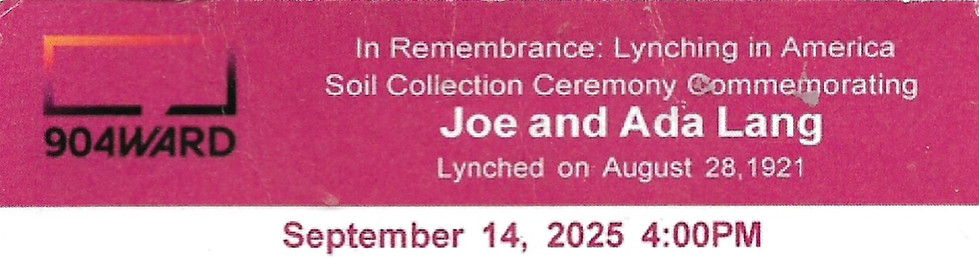

In 2019, Mrs. Maliza Lang McMillan; the Langs’ great-granddaughter and granddaughter of their son, Emery; requested the Jacksonville Community Remembrance Project’s (JCRP) inquiry into the lynching of the Langs. The JCRP is an initiative of the local social-justice and equity nonprofit 904WARD. Maliza Lang McMillan came to the JCRP asking for help to find the property of her great grandparents, as well as to make any contact with the family of the suspected perpetrators. She was directed to me, and it was suggested I conduct an oral history with her. I conducted Mrs. Lang’s oral history in 2019.

The family of Maliza Lang McMillan was the subject of several newspaper stories in 1921 after the murders of her great-grandparents, Joe and Ada Lang.

During the oral history, she stated that her great-grandparents owned a “pulp company,” which included 88 acres of land.

The story goes like this: In the early morning hours of August 28, 1921, Joe Lang saw a fire in the barn of his mid-sized farm. When he went out to investigate, he was and killed. He fell down near the fire. When his wife opened the window to see what happened, she was shot as well. Their six children scattered to the winds that terrible night. Taken to Brewster Hospital, Ada Lang died of her wounds two weeks later on September 10. Their 19-year-old son, John Lang, in trying to rescue his father, was also fired upon but escaped injury. His brother, Emery, 16, witnessed the perpetrators, cousins John Thomas and William Arthur Higginbotham, armed, “standing at the edge of the sugar cane patch”, but in court failed to identify them. But what happened to the other children? This article from the Florida Metropolis provides more details to the story . . .

The Tampa Tribune

December 3, 1921

The trial, held December 1-3, 1921, ended in a verdict of “not guilty” following jury deliberation of one hour and five minutes. Newspaper articles covering trial testimony state that on the Saturday before the murders, John Higginbotham presented warrants to the Sheriff, demanding the arrest of five members of the Lang family and that, at that time, he threatened their lives. The Sheriff decided to postpone service of the warrants until Monday, but the shootings occurred on Sunday. Death certificates show that both Ada and Joe Lang died of gunshot wounds and that they are interred at Jacksonville’s Memorial Cemetery.

Through the outreach of the Jacksonville Community Remembrance Project, the great grand-daughter of Joe and Ada Lang, Maliza Lang McMillan, heard about its Oral History Project. Mrs McMillan's father was haunted to his last days by the fact that he knew so little about his own father, Joe and Ada's son, Emery. I was honored to conduct the Lang family oral history.

The JCRP Research Committee searched for the property Mrs. McMillan's family lost and the rest of her family members for years, even though the search was suspended by the COVID pandemic in 2020. By 2023, I was co-chair of the JCRP, and began planning a soil-collection ceremony for the Langs. Soil-collection ceremonies were integral to the creation of the JCRP. In 2001, the Atlanta-based legal-justice organization Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) began a program of documenting any and all instances of racial-terror lynchings in America, defining that term as "lethal violence directed at people because of their race in an effort to terrorize the entire community." EJI started a program by which communities began “remembrance projects” to document these incidents, research possible lynchings in their area, and then report them to EJI. Once approved by EJI, CRPs were directed to conduct soil-collection ceremonies to honor the victims of this violence. They could then apply to have historical markers installed in those spots. The JCRP has already installed one such marker in the city of Jacksonville and has conducted eight ceremonies to collect soil from the scenes of these crimes.

When the JCRP began having in-person meetings again in 2022, we were lucky enough to find the property through the work of Joel McEachin and the Jacksonville City Planning Office. The Old Lang farm was located in a little creek between a housing development and some property owned by Jacksonville Councilmember Mike Gay near Dinsmore off of Old Kings Rd. CM Gay was gracious enough to allow to hold the ceremony on his property on September 14, 2025 at 4pm.

Thank you to Alex Rudnick and Audrieanna Burgin for creating a ceremony that both truly honored this Jacksonville family as well as acknowledged the wrong done to them.

property on September 14, 2025 at 4pm

property on September 14, 2025 at 4pm

Strange Fruit Pt.2

by David Jamison

Trees

In the South

Bear quite a strange fruit.

Coarse, rough fibers, Twisted,

Lead to glistening flesh. Blood and sweat Trickle down over

Once-proud chests and torsos.

They flume through abdomens,

and bear witness to castrated glory. They shoot down hefty thighs

And drip off of dangling toes, Swaying inthe hot, southern wind.

Trees in the South Seem to be made of Gnarled, knotted wood

That brahch sideways

And reaches forever to the horizon.

Southern children

Do not pick this fruit.

They only gaze up in wonder, Shrug,

And do a crude dance around these

Baffling woods (an awkward imitation of what they saw their parents do the night before).

The landscape is barren.

These trees vegetate in burnt-up grasses,

But the hate and anger that seeds this crop Still smolders in the warm earth.

Smolders, embers in the plow-down earth.

And only ravens and crows On this fruit feed.

They gorge themselves on horror, And revel in the bouquet of decay. And even these blackbirds

Veil sympathy. They cannot turn

Feathered eye from animal indecency. And so they feast reluctantly,

Happy in their satiety,

And appalled in their gluttony.

And the sun lays a dusky, murky, Purplish hue over the whole scene.

Trees

In the South

Bear princes from far-off lands. They bear a statesman here,

A carpenter there.

They bear the hopes and dreams Of a young African mother.

They bear the respected idol Of brown-eyed angels.

Southern trees bear

World conquerors and scholars, Writers and painters,

Fathers and sons.

Trees in the South

Bear the perverted destinies Of generations to come.

And one wouldn't expect to be able to nimbly pluck such fruit off of any old tree.

One would expect such fruit to Walk up to me,

And shake my hand, And call me "friend."

One would expect such fruit to realize expectations, To fulfill potentials;

To right what was once put wrong.

One would expect such fruit to realize master plans; To fall inlove;

To marry the girl next door in an overly long ceremony.

One would expect such fruit to become indignant at the world's state of affairs, arguing at the top of his lungs from the stoop with the neighborhood know-it-alls.

One would expect such fruit to live to a ripe old age,

Falling absent-mindedly asleep On the front porch.

But this fruit just sways

In the hot, southern wind. And drips blood and sweat

On the heads of dancing children.

Strange fruit, indeed.

Councilmember Rahman Johnson was gracious enough to come by for a special Proclamation!

Volunteer historian Mary Breitenbach was on the research team since 2019 and provided invaluable insights and discoveries that were key to the Lang case